Go wild with Sir David Attenborough

People who spend any time in the UK soon learn about the special place that Sir David Attenborough occupies in the nation’s affections. The science broadcaster, natural historian and author has been a fixture in the UK for almost as long as the Queen, and is similarly beloved. At 96, his latest nature documentary, The Green Planet, is premiering this month on PBS – and he is still at the forefront of factual broadcasting nearly 70 years after he first started.

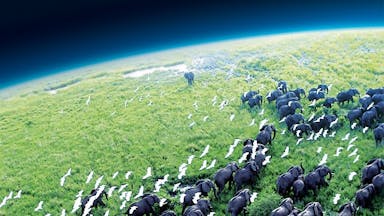

Attenborough more-or-less invented the nature documentary as we know it today. His first came in 1954, only two years after he joined the BBC. Due to a presenter’s illness he stepped in at the last minute to present a show about zoo animals, and an epic career was born. He soon took the show out around the world, delighting viewers with footage of exotic places and exciting animals, and followed that with a series of ambitious, globe-spanning shows that explored the entire planet and its evolution. 1979’s Life On Earth established the formula, combining natural history with extraordinary photography by the BBC’s Natural History Unit. Attenborough and the team built on that with 1985’s Emmy nominated The Living Planet, and shows like The Private Life Of Plants – a forerunner of other efforts, such as Life In The Undergrowth and The Green Planet.

Attenborough’s genius lies in the combination of passion and knowledge that he brings to each programme. He doesn’t talk down to the viewer, but explains scientific concepts in a measured pace and with an unfailing sense of enthusiasm and humour. Travelling around the world to visit the animals and landscapes that he describes, Attenborough sometimes made himself the butt of the jokes, letting baby gorillas clamber all over him, being attacked by a large grouse or cooing at a strutting bird of paradise. While he’s done less globe-trotting since he passed retirement age, he has spoken out more in defence of endangered species and habitats, and almost single-handedly swayed the UK against plastic straws in Blue Planet II.

For technology rather than nature geeks, Attenborough is also the quintessential early adopter. He’s the only person to have won BAFTA Awards in black and white, colour, high-definition, 3D and 4K resolutions, for shows including Planet Earth II, David Attenborough's Natural History Museum Alive and Frozen Planet. Both Blue Planet and Planet Earth finished each episode with a look behind the scenes at how their fearless camera crews captured intimate footage of vanishingly rare creatures, which is sometimes almost as impressive as the animal footage.

After 70 years in television – where he also first commissioned Monty Python’s Flying Circus, incidentally, while he headed up BBC2 – Attenborough has only become more impassioned and productive with age. The documentary David Attenborough: A Life on Our Planet focuses not just on his natural history work, but also the changes to our planet during his lifetime, contrasting footage from his first expeditions in the 1950s with modern landscapes. Rather than burnishing his own myth, he’s using his achievements to draw attention to bigger issues, including climate change, for which he issued an ‘act now’ warning ahead of the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow last year.

It's that sort of passionate devotion to life on Earth that has made Attenborough so beloved here in the UK and all over the world. His instantly recognisable voice is a hallmark of quality, a promise that you’re going to see something you’ve never seen before, and learn about things you never knew existed. It should be noted that in the US, both the soundtrack and commentary of some Attenborough series were re-dubbed to appeal to US audiences. However, despite an impressive cast of alternative star presenters, the original Attenborough versions remain popular and available for streaming, alongside his latest work.

Attenborough himself makes light of his national treasure status, wincing at the term and narrating comedy bits for, say, Adele videos instead. But for everyone else who has grown up listening to and learning from him, he’s a serious inspiration.

As the man himself said: "It seems to me that the natural world is the greatest source of excitement; the greatest source of visual beauty; the greatest source of intellectual interest. It is the greatest source of so much in life that makes life worth living."